A young man

tortures another young man. One super-hero flies through the air and massacres

some bad guys, whilst another murders a protester.

Game of

Thrones has officially become a cultural juggernaut. Season 3 managed to semi-consistently

pull over 5 million viewers (pretty spectacular for a modern series), and the

twists and turns have become prime watercooler conversation. One of the elements

that has certainly helped to boost viewership is violence. Looking at reviews or

summations of the series, the word which comes up the most is probably “brutal.”

In particular, the series isn’t shy about treating relatively central

characters with vicious disregard. That, in and of itself, has probably allowed

it to shed much of its geeky image.

“Bro… bro!

You need to check this show out. People get fucked up. Yeah, I know it’s

fantasy, but it’s like totally dark.”

Also, tits.

One can only hope

As anyone

who knows me will tell you, I like violence (and who doesn’t?). However, I’m

actually going to come down on the side of moderation. Regarding storytelling,

violence is a delicate thing that needs to be used at the correct time and in

the correct context. Something which can be an indicator of character or

purpose in one setting, is merely boring or unpleasant in another.

This will

discuss spoilers regarding the latest season of Game of Thrones, which if you

didn’t watch, you almost certainly had ruined for you. So consider that this

spoiler warning is for the rare, unicorn-like individual who is even

tangentially interested in it, and doesn’t know that Simon from Misfits is actually secretly Old Man Withers, the

amusement park owner.

I will also

be spoiling Watchmen, and Kick-Ass.

************SPOLIER

WARNING**********

When Violence is Dum / Gross

The Theon

Story. Holy smokes, this was terrible. TERRIBLE.

I generally

try to avoid “X source material is sooo much better than the remake” nerd

snobbery, but why the writers of the show chose to jettison most of the

elements of the “original” Theon / Ramsay story in the first place is somewhat

confusing. Whatever the reason, they stuck themselves in this situation, in

which Theon is captured and cannot escape for at least a season. There were, at

least, reasons for keeping him as a presence in the show, namely to keep from

him being forgotten in a swathe of new characters and storylines, and to keep

his (excellent) actor tied to the project.

However,

the season 3 scenes were almost universally derided by almost everyone I spoke

to, and with good reason. Each segment with Theon and his tormentor played out in

a woefully predictable way, with the torturer being mean to him, and then Theon

getting brutalized and whimpering.

This was

the television equivalent of pulling wings off flies. One of the key elements

to making fiction shocking is to actually shock,

to surprise the viewer. True horror gives the viewer hope, and then takes it

away. The scenes were thick with a dreary sense of inevitability- Theon has no

power, no chance of escape, and we simply watch as he gets tortured.

This is

essentially the difference between the first Saw film, which is pretty good,

and the subsequent 15(? Conservative estimate), which are just horrible things

happening to people in between batches of convoluted gibberish in a spooooky

voice.

It is

possible to make entirely downbeat, unpleasant fiction about awful situations and have it still be engaging to some extent. A good example of this

is Hiroaki Samura’s Bradherley no Basha, which is about…. Urgh. But it does

tell stories, and manages to evoke emotions, and genuinely raise the spectre of

hope (I still wouldn’t exactly recommend

it to anyone). The emotions most often evoked by the Theon scenes were a vague

sense of being grossed out, and boredom.

Bradherley no Basha. Blargh! Yuck.

The second section

where I felt like the series crossed the line was during the infamous Red

Wedding. I don’t have as much to say about this, but Tulisa getting stabbed

multiple times in the stomach was just unpleasant. The reason why the Red

Wedding was such an iconic cultural moment wasn’t (just) because of the

violence, or the brutality. It was because it happened to characters which the

viewers had gotten to know over the course of three seasons of television. The surprise

came from their deaths, not because their deaths were particularly vicious.

Having a pregnant woman being gutted didn’t add any more shock to the scene,

because that’s barely possible. It just added a slight tinge of tacky

exploitation to what was otherwise a masterfully handled, nail-biting scene of

absolute horror.

George R R

Martin, the writer of the original series of books, has fielded his own share

of criticism about some of the violence and mutilations. A common counter to

these criticisms is one of “historical accuracy” – he’s trying to make the

series realistic and gritty, and terrible, arbitrary things happened to people

in the past. The obvious refutation to make is that the books are fiction, and therefore can be judged under

the constraints of structure. If I wanted to read about terrible, arbitrary

things I could just read a history book.

Regarding

structure, for all the talk of the revolutionary, genre-busting nature of GoT /

aSoIaF, it is fundamentally a fairly traditional story of Ice Scots versus

Dragons, with a hero’s journey or two thrown in there. It has merely been (overly) fleshed

out with politicking, and redheaded chicks, and so on. Thus, when Martin decides to, say, make an

already-ugly character even uglier with the addition of some hideous facial

scarring, it’s OK to point at that decision and say “Hey, what was the point of

that, George?”

When Violence Fails in Illustraten Character

Jumping to

a wildly different tangent, let’s look at Mark Millar’s Kick Ass. The sequel to

the successful super hero film is coming out soon, and the original was

generally well-received. Millar is an interesting figure, who has been involved

in writing comics for a long time. I actually used to read some of his stuff in

2000AD as a nipper, including Cannon Fodder (a gun wielding priest teams up

with Mycroft Holmes to stop Sherlock Holmes from killing God. It’s difficult to

express how much more uninteresting this actually was, compared to how it

sounds), Maniac 5 (…Robocop), and Babe Race 2000.

Babe Race 2000. Exactly what it sounds like.

In recent

years, he’s become a far better writer, and a powerful figure in the comics and

even film industries. Much of the success of updating the Avengers franchise

can be laid at his feet (his Ultimates series was essentially the blueprint for

the first film, he “cast” Samuel L Jackson as Nick Fury etc). He has a knack

for making cinematic stories, and a whole bunch of his properties have been

made into films, including Wanted, and, of course, Kick Ass. He does a good-sometimes-great

job of blending action with twists, and can actually make interesting, popular

work, which is much harder than it sounds, and something that a great many

filmmakers and writers fail at.

He’s a little like a comic book analogue of Quentin Tarantino, whom I wrote about in my

Django review. However, he does not have Tarantino’s auteur aspirations- his

work is geared towards popularity with a singleness of purpose that is almost

refreshing. Bombast and excess are Millar hallmarks. Everything is AWESOME! Or

CRAZY! Or, yes, SHOCKING! A bludgeoning salesmanship is constantly present, and

is backed up by a disconcertingly broad streak of misanthropy and

self-loathing, where he demands that the reader buy his book whilst

simultaneously excoriating them for being a loser nerd. Quickly dated

pop-culture references are rife, and if he’s written anything recently, I would

bet money that it references Game of Thrones, and probably Yeezus.

Kick Ass is

a story of a young man who decides to become a super hero. It is a very violent

film, but is toned down from its original comic. The sequel will almost

certainly deviate further from origins, because it’s going to have to. Even given that, Jim Carrey has apparently distanced himself from the project now that it has wrapped due to the levels of violence. Millar is

not shy about using things like rape as plot devices, and has basically no

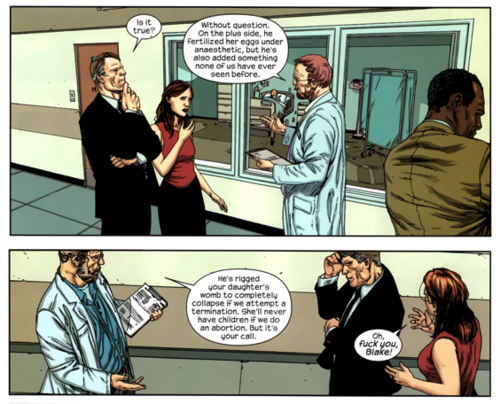

depths to which he won’t sink. Take this scene from one of his other products,

for example, where the bad guy kidnaps the hero's daughter, and artificially inseminates her with her gay brother's semen. Sound unbelievably ridiculous? But wait! There's more!

gggghhhhhhh

I’m torn

between contempt, laughing at how stupid it is, and a weird kind of grudging

respect at the balls or self-delusion required to actually put something that ridiculous down on

the page. Womb rigging. For Christ's sake. This is also being made into a film, by the way.

This is not

to say that Millar is stupid, far from it. The final scene from Kick Ass

involves the titular hero and sidekick/heroine/young girl psychopath Hit Girl

(she swears a lot! And kills tons of people! Extreme! Buy it loser buy buy buy) storming a mobsters hideout.

There’s a significant difference between the film and the comic. In the comic,

Kick Ass relies on his trademark tonfa sticks throughout the entire fight,

whereas in the film he dons a weird flying suit with miniguns attached, and shoots

a variety of villains to stirring music, before killing the main bad guy with a

rocket launcher.

In the

larger context of what has been a ridiculously violent movie, this shouldn’t

seem so bad. However, it fundamentally goes against the entire premise of the

story, which is this: what if an ordinary

guy tried to be a hero like Spider-man?

Kick Ass is

an innocent, and part of the charm of the story is seeing how he firmly keeps

to the non-killing ideals of a hero, despite being humiliated, beaten, and surrounded

by murderous lunatics. That he becomes a murderer like them in the film’s

climax is just… sad. James Gunn’s Super, a (better) film with a similar set-up

and premise, also has a violent slaughter as its final act. It functions a lot

better, however, as the entire story makes no bones about its main character

being an extremely disturbed individual who treads the line between heroism and

insanity.

Alan Moore

is arguably a marginally better writer than Mark Millar. Like Millar, many of

his works have made their way to the silver screen. Unlike Millar, none of them

have done so with his blessing. Of all of them, the most faithfully transcribed

was the Watchmen adaption helmed by Zach Snyder. Many die-hard fans hated it,

but to be fair they were always going to. Personally, I thought it was

enjoyable, and for the most part about as good as it was ever likely to be.

Some of the problems with it were simply inevitable consequences of being a

Hollywood production – the super heroes looked cooler, and their action scenes

were slicker, partially because of Snyder’s own proclivities but also because

Hollywood execs have certain expectations which must be met. Wheezing

semi-comical middle-aged people in spandex would raise eyebrows, but not any

kind of funding. Similarly the squiddy climax of the comic simply could not be

leveraged into a film without leaving any audience unfamiliar with the source

material confused and alienated.

I did have

my problems with the film, but I didn’t find that they were shared by that many

people. I thought that the actor who played Rorschach looked exactly like him,

but misread the role horribly. I also had a very specific issue with one of the

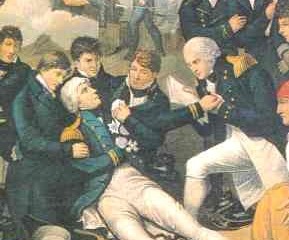

scenes with The Comedian, where he and Night Owl are quelling an anti-hero

protest / riot.

One of the

protestors runs up to The Comedian, and he blows him away with a shotgun. Unlike

Kick Ass, The Comedian is specifically the most amoral, callously violent

character in his story, and is involved in several extraordinarily brutal

scenes, like the rape of Silk Spectre and the murder of the pregnant mother of

his child in Vietnam(!). So why did this specific scene annoy me? Because once

more, it betrays or ignores elements of character.

I’m not

Alan Moore and I don’t know what he’s thinking, but if I had to guess at the overall ethos of The Comedian, it could be summed up in one exchange (ironically,

in exactly that scene) where Night Owl asks: “What happened to the American

Dream?” and The Comedian points a thumb to his chest and says: “It came true.

You’re looking at it.”

The

Comedian is an American. He is a

cynical, ruthless extension of American culture, a dark parody of the action

hero, and a product of US isolationism and the patriarchal jingoism of the

post-war era. He wears the American flag, rescues Americans in hostage

situations, and weeps when he finds out that millions of Americans are going to

die. The people he kills are Vietnamese and (if he has in fact killed Hooded

Justice, and he is Rolf Muller) German, historically enemies of the US. He may brutalize fellow Americans, but he does not kill them.

Moore goes out of his way to specify that The Comedian is

carrying non-lethal weapons, and when Alan Moore specifies things in stories, it’s generally

best to pay attention. These are the subtle

differentiates between a bad character who has good elements, and a twisted

vision of the Nixon-era American ideal.

“I Hope They Don’t Tone This Down”

All three

of the stories mentioned above were infamous for being dark and violent in their

original incarnations, and one of the frequent worries when particularly

controversial works are adapted on to the screen is that the adaption will

“tone it down.”

What isn’t

often noticed is when the adaption doesn’t tone it down enough, when it misses those crucial moments when the author held

back. George Martin and Mark Millar are tacky dudes, who even share a weirdly specific way of trying to gross

people out by having a man and his beloved canine swap heads, but they understand

the value of restraint. Martin knew, even given how woefully bloated the

Song of Ice and Fire series can get, that no-one wanted to read pages of

torture scenes. Mark Millar might come across as a twelve-year-old who calls

his villains The Motherfucker and The Toxic Mega-Cunts, but he knew that

retaining some sort of essential goodness or even naivety to his protagonist

was a superior story choice (Yes, I do know that he went on record as saying

that he approved of the ending of the Kick Ass movie, but I refer you back to the

part where I talked about his naked commercialism).

Alan Moore is quite good at

writing good, and has a large beard.